Party: Democrat, Southern Rights.

Residence: Paris, Bourbon County.

Occupation: Lawyer and Farmer

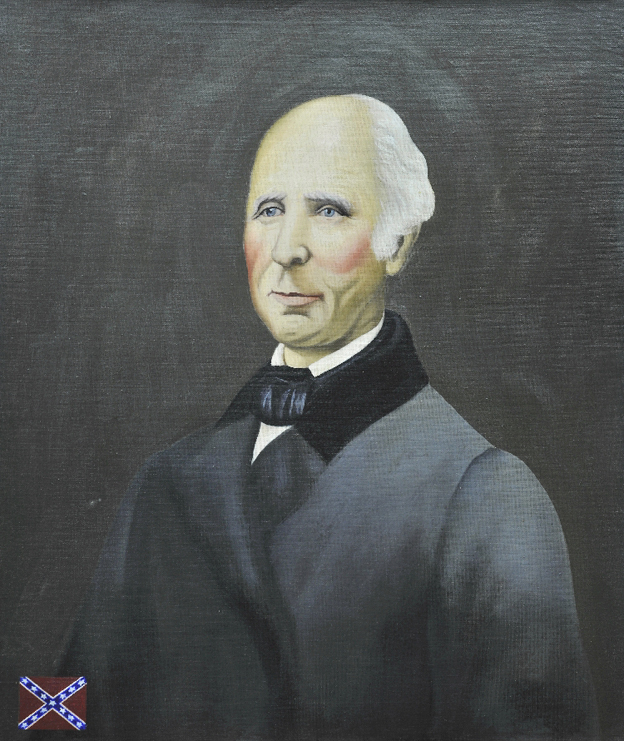

Confederate Provisional Governor Richard Hawes was at the center of one of the most dramatic moments in Kentucky history. In October 1862, with a Confederate army at his back, Hawes entered the Old State Capitol, was sworn in as governor, and gave a rousing inaugural address. The moment, though, was fleeting.

Confederate Provisional Governor Richard Hawes was at the center of one of the most dramatic moments in Kentucky history. In October 1862, with a Confederate army at his back, Hawes entered the Old State Capitol, was sworn in as governor, and gave a rousing inaugural address. The moment, though, was fleeting.

A generation older than Kentucky’s other Civil War-era governors, Hawes came to the Bluegrass from his native Virginia, living and working as a lawyer and part-time hemp planter in Lexington and Winchester before eventually locating to Paris, Kentucky. He began his political career as a Whig disciple of his distant relative, Henry Clay, eventually serving one term in Congress. After the Whigs collapsed under the weight of the issue of slavery in the early 1850s, though, Hawes found a new home in the Democratic party.

When the war came, Hawes fled to Virginia and took up a position as a Confederate staff officer. After George Johnson was elected the state’s first provisional governor, he requested that Hawes join him in Bowling Green, the new Confederate capital, to help administer the government. Hawes accepted, but took ill before he could play any active part. Compounding the crisis faced by the Confederate provisional government of Kentucky which had been forced to abandon the state in February, 1862, George Johnson’s death at the battle of Shiloh in April left the organization without an executive. According to the rules adopted by the secession convention at Russellville, it fell to a governing council of ten members-who were to assist Johnson until a new Confederate legislature could be elected and installed-to elect a replacement for the provisional governor if a vacancy should occur. Forbidden from choosing one of their own, the council elected Hawes.

Though the tide of war in the spring of 1862 had exiled the Confederate government under Johnson from Kentucky, a Confederate offensive that summer and fall afforded Hawes a chance to return and perhaps seize control of the entire state. When rebel armies drove virtually unopposed into Kentucky in August and September 1862, Hawes and the provisional government followed quickly behind. Disappointed by the unenthusiastic reception that the rebel troops received in Kentucky, Confederate commander Braxton Bragg hoped that a grand political gesture might lead the state to rise up against the United States. Veering off from an advance on the strategically important and poorly defended city of Louisville, Bragg marched on Frankfort to finally install Hawes at the legitimate seat of government.

In the midst of the ceremonies, Union artillery fired on the town, heralding the approach of a much larger force. The rebels abandoned Frankfort before the inaugural ball could be held. Less than a week later, a Confederate tactical victory at the battle of Perryville left rebel forces too weakened to continue operations in Kentucky. Hawes left Kentucky as Bragg’s forces fell back, never to return to Kentucky during the war. Hawes and the provisional government joined the refugee community of prominent Kentucky secessionists and their families, living with friends and family in the Confederacy. After time in Tennessee and Georgia, Hawes eventually returned to stay with family in Virginia, not far from Richmond where he could lobby Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government on behalf of rebel Kentucky soldiers, and the silent majority of sympathetic citizens whom they continued to believe-by and large erroneously-lay at home under Union occupation.

Returning to Kentucky in 1866, Hawes became a judge, issuing rulings that undermined the efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau in the state, and was an active participant in Democratic politics until his death just over a decade later. Because he spent his term mostly out of state and frequently on the move, CWGK’s Hawes collections are thus far the smallest of any governors. What does survive, however, affords fascinating new access to the inner world Confederate national politics and of the thousands of refugee rebel Kentuckians. Hawes’s exile and wartime mobility requires that CWGK conduct exhaustive searches in the archives and libraries across the former-Confederate states to compile as broad a documentary base as possible.