Party: Whig, Union Democrat.

Residence: Columbia, Adair County.

Occupation: Lawyer and Judge

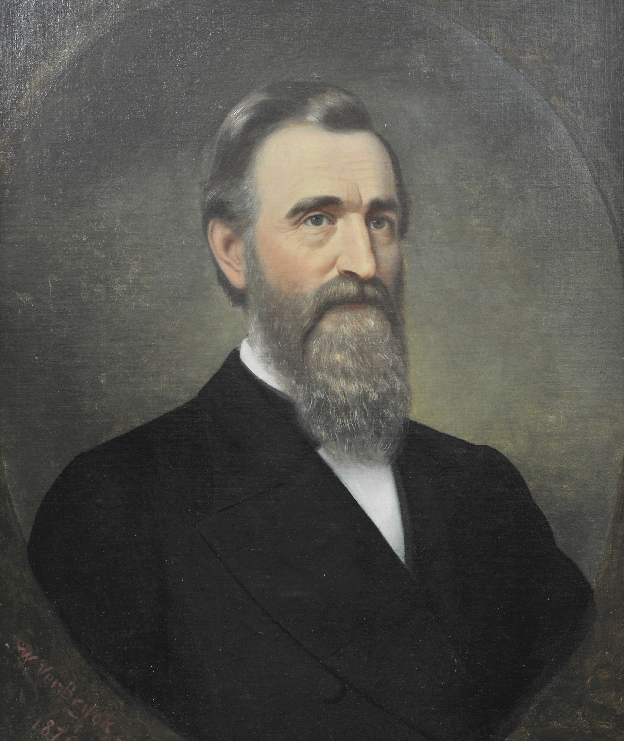

Thomas Bramlette’s administration was the longest of the five CWGK governors and is the best documented. It is fortunate that Bramlette’s time in office is so well represented. As the war’s significant military action shifted to the outskirts of Atlanta and Richmond, Kentuckians during the Bramlette years were arguably more politically splintered, plagued by violence, and uncertain about what a looming postwar, postslavery future might mean than they were at any other time during the war.

Thomas Bramlette’s administration was the longest of the five CWGK governors and is the best documented. It is fortunate that Bramlette’s time in office is so well represented. As the war’s significant military action shifted to the outskirts of Atlanta and Richmond, Kentuckians during the Bramlette years were arguably more politically splintered, plagued by violence, and uncertain about what a looming postwar, postslavery future might mean than they were at any other time during the war.

Bramlette was one of the first men to leap to the defense of the old flag, even before Kentucky’s neutrality ended in the fall of 1861. He raised the Third Kentucky Infantry Regiment in the southern Kentucky counties surrounding his home, but Bramlette’s military career was not a lengthy one. He resigned in July 1862 to become a U.S. District Attorney.

Bramlette was elected during an election season dominated by debate over Kentucky’s role as a slave state and a loyal state. Dissatisfied in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation, most white Kentuckians opposed the rebellion but neither were they enthusiastic about the federal war effort if it meant further erosion of slavery. Union Democrats searched desperately for a candidate after their first selection, Joshua F. Bell, withdrew his name after the nominating convention had met. Scrambling, the party chose Bramlette, who won in a bitter contest that saw some supporters of his opponent, former governor Charles Wickliffe, jailed by state and federal authorities for suspected Confederate sympathy.

Bramlette tried to strike a moderate tone that would play to both unhappy loyal masters and the Lincoln administration. Appealing to moderate antislavery men in the state, Bramlette encouraged Kentuckians to regard slavery as it was, a dying institution, and to plan for rebuilding the state on the basis of free labor. Attempting to assuage the anger of loyal masters who were urging resistance to the federal government’s antislavery policies, though, Bramlette also resisted any extension of civil rights to African Americans. Though it may seem odd that Bramlette simultaneously opposed slavery but resisted citizenship for African Americans, his position was quite common across the loyal states among people-Republicans and Democrats alike-who despised slavery as an institution yet also harbored deep, racially motivated mistrust of African Americans as individuals.

As principal intermediary between Kentucky and Washington, D.C., Bramlette had to balance the desires of loyal Kentucky slaveowners with the demands of the United States war effort. No other issue was so fraught with political peril as African American recruitment into the Union army. Initially, Bramlette and the state’s conservative proslavery leadership argued that allowing black men to serve in the army was the first step towards black citizenship, and mustered heated states rights rhetoric to defend Kentucky’s traditional purview over the state’s African American population. The Lincoln administration was not amused, and arrested a number of Bramlette’s political friends, including the Lieutenant Governor, R.T. Jacob. Yet, months later, when African American recruitment was an accomplished fact, the Bramlette administration cooperated with federal military authorities to claim credit for the service these black Kentuckians so that white men in the state would be exempted from the draft.

Bramlette had more to worry him than battles with Washington; during 1864 and 1865 Kentucky descended into chaos. Fueled by racialist resentment to the new freedoms asserted by African Americans and anti-government attitudes, bands of guerillas organized across the state. Some were nominally affiliated with the Confederate military, but most acted as law unto themselves, robbing and murdering their neighbors. Bramlette raised thousands of troops into state service to combat the guerillas, and while some saw success, most were ineffective. The worst of the state soldiers became partisan warlords themselves.

Bramlette oversaw both the end of the war and the end of slavery in Kentucky. Neither ended cleanly. Racial hostility and guerilla violence eventually coalesced into a proto-Ku Klux Klan reign of terror by the end of his term-prompting a massive exodus of black Kentuckians to states where personal safety and rewarding labor were easier found than at home. Though Bramlette himself seems to have genuinely mourned Lincoln’s death and admitted that the President had been right about the necessity of emancipation to end the war, white Kentuckians who dominated the legislature flatly refused to grant any civil rights to African Americans in the final years of Bramlette’s term. Though CWGK will only publish Bramlette’s papers through December 1865-when slavery was officially ended in Kentucky by the Thirteenth Amendment-his papers tell the fascinating story of a society whose foundations collapsed into a new-if perilous-birth of freedom.