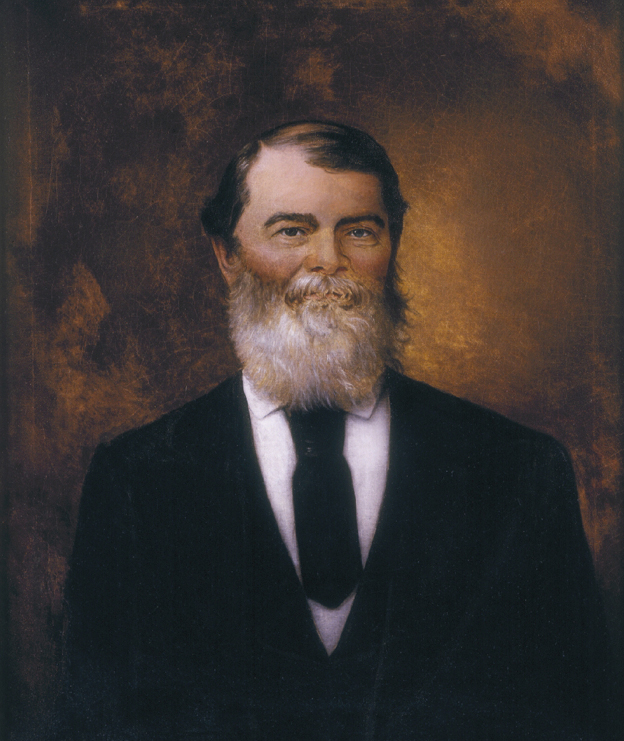

Party: Democrat, Southern Rights.

Residence: Harrodsburg, Mercer County

Occupation: Lawyer and Farmer

Like many Kentuckians, Beriah Magoffin found himself torn between his interests, sympathies, and loyalties during the secession crisis. He joined most white Kentuckians in opposing Lincoln's election in 1860, but joined the conservative proslavery majority in the state-roughly two-thirds of the voting population-to advise against secession and rebellion while still hoping to protect the rights of slaveholders at home and in the territories. His December 1860 exchange with Alabama Secession Commissioner S.F. Hale is a classic statement of Kentucky's anti-secessionist pro-slavery philosophy-a great irony in light of his eventual sympathy for the Confederate cause.

Refusing Lincoln's April 1861 call for volunteers to suppress the rebellion, Magoffin led Kentucky into a period of official, armed neutrality. For months, the state militia refused to allow United States or Confederate military personnel into Kentucky, while political battles raged in a legislature divided over the question of secession. Magoffin's not-so-secret secessionism won him no favors with the emerging Unionist majority as 1861 wore on, particularly among the former-Whigs who resented seeing a Democrat in the governor's mansion.

After Unionists captured the legislature in August and declared Kentucky's unconditional loyalty to the United States in September, they set about relieving Magoffin of many executive powers. During the spring, the legislature had created a Military Board, with Magoffin as president, to oversee the state's armed forces. Yet after September, fearing that Magoffin would delay the recruitment of loyal troops, the governor was demoted, first to a voting member of the board and later removed altogether. The relationship between the General Assembly and the governor remained sour. Magoffin routinely vetoed war measures only to have his veto overridden by the loyal majority time and again. As Confederates invaded the state in the summer of 1862, Magoffin was pressured to resign. He did, but only on the condition that he hand-pick his successor, State Senator James F. Robinson-a Unionist but one committed to protecting the interests of slaveowners. Magoffin largely removed himself from wartime politics, spending the war at home or overseeing business in Chicago, though he later served one postwar term in the General Assembly.

Magoffin's papers make an excellent place to begin understanding how Kentuckians reacted to and shaped the secession crisis. In addition to his personal communications with Washington, neighboring governors, and the legislature, nearly every part of his official papers testify to the deep divisions within the state. Military commissions are sought by men hoping to put down the rebellion and resigned by officers going to fight for it. Notes of support for both the Union and the Confederacy appear on pardon petitions and applications for notaries public. Magoffin's papers, too, provide CWGK's best glimpse of the last few months of antebellum slavery in Kentucky. Through these records, we see traces of an Upper South slave society alive and well, before rumors of emancipation, invading armies, and the assertiveness of enslaved Kentuckians began to weaken slavery across the state.