Party: Whig, Unionist.

Residence: Georgetown, Scott County.

Occupation: Banker and Lawyer

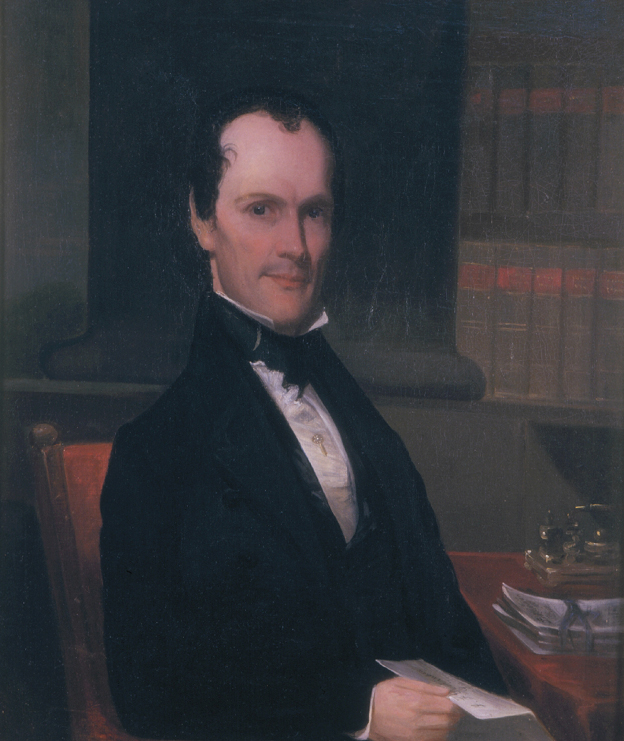

It is tempting to see James F. Robinson’s short term as governor as an interlude between the excitement of Magoffin’s secession crisis and Bramlette’s titanic battles with the Lincoln administration. Robinson’s administration, however, spanned the year on which all of Kentucky history arguably turned-the pivot point when slavery began to collapse along with the faith of many white Kentuckians in the federal government. He was elected via a legislative coup, first retreated from and later repelled a major Confederate invasion of the state, and set the tone for conservative Unionist resistance to Washington’s emancipation measures.

It is tempting to see James F. Robinson’s short term as governor as an interlude between the excitement of Magoffin’s secession crisis and Bramlette’s titanic battles with the Lincoln administration. Robinson’s administration, however, spanned the year on which all of Kentucky history arguably turned-the pivot point when slavery began to collapse along with the faith of many white Kentuckians in the federal government. He was elected via a legislative coup, first retreated from and later repelled a major Confederate invasion of the state, and set the tone for conservative Unionist resistance to Washington’s emancipation measures.

Robinson was elected to the State Senate in the August 1861 election that finally secured Kentucky for the Union cause. Though Robinson was one of Magoffin’s ex-Whig Unionist opponents in the legislature, when Magoffin was being pressured to resign in August 1862 he would only do so if Robinson replaced him. The gubernatorial line of succession was complicated. Magoffin’s Lieutenant Governor, Linn Boyd, had died in 1859, just over a month into the term, making the Speaker of the Senate next in line. But Magoffin thought the sitting speaker-John Fisk, a New York native who represented Covington-insufficiently conservative and worried that Fisk might too zealously crack down on secessionists or inadequately defend the property rights of slaveowners. With a solidly proslavery record and hailing from a county with large numbers of rebel soldiers and sympathizers, though, Robinson was acceptable to the governor. So, over the course of just two days, Fisk resigned; Robinson was elected speaker; Magoffin resigned; Robinson became governor; and the former speaker was re-elected. This seemed to all be nominally constitutional, though Robinson never resigned his seat in the Senate and technically held both that and the governorship simultaneously.

The new governor immediately found himself in a critical situation. Two major Confederate armies slipped around and through Union defenses and invaded the state within months of his election. As one of those armies, containing Confederate provisional governor Richard Hawes, marched on Frankfort, Robinson was forced to abandon the capital and flee to Louisville. Hawes was inaugurated at what is now the Old State Capitol, but the rebels did not stay long. Union armies converging from the south and north drove the Confederates from the state after the battle of Perryville-the largest and most significant Civil War battle fought in Kentucky-in early October.

Robinson presided over a state forever changed by that invasion. Not only had the rebels hauled away a wealth of Kentucky food, goods, and livestock, but the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation shook Kentucky’s slave society to its core. Though the proclamation did not apply to loyal Kentucky, enslaved people took it as a sign that slavery was coming to an end. They often found allies in Union reinforcements sent from northern states to repel the Confederate invaders. Unionist slaveowners were outraged when federal military officials sat silent as thousands of enslaved Kentuckians found refuge within Union lines, and from that time on both the institution of slavery and the faith of many white Kentuckians in the federal government went into a steep decline.

Both as governor and, later, when he returned to the Senate, Robinson proved the articulate defender of the legal rights of slaveowners that Magoffin had hoped he would be. His finely crafted constitutional arguments, though, stood little chance against the historical tide which had been turned during his administration. His papers are CWGK’s window into one of the most important crisis years in Kentucky history.